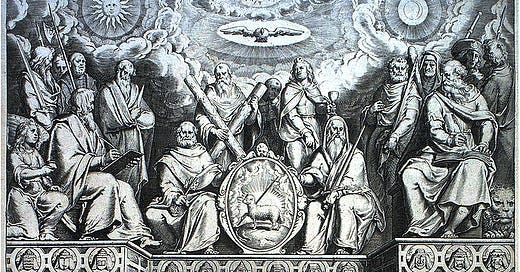

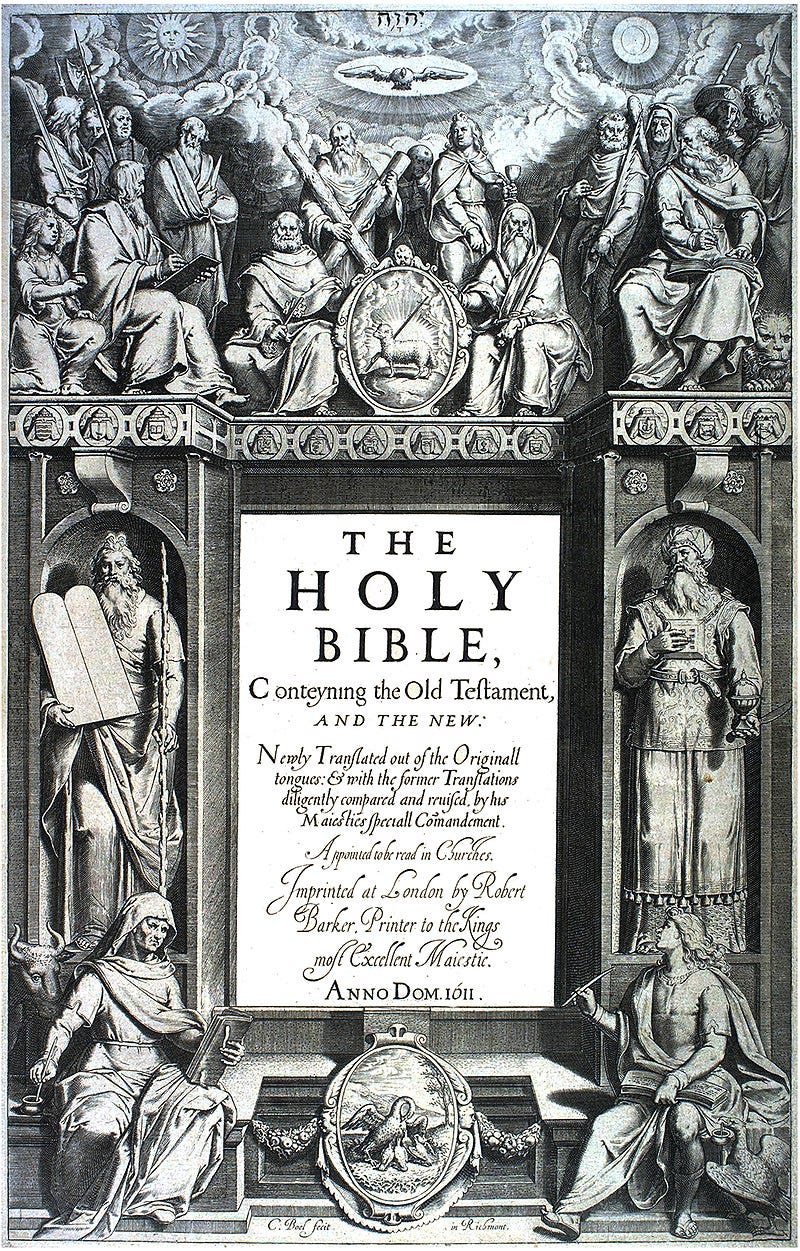

Before launching into my own readings of the biblical texts, I should lay out some preliminaries. First, by “the Bible,” I mean both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament considered as a unit. I use the Christian canon for the simple reason that I am a Christian and because of the literary and historical importance of the New Testament. That said, the method I follow below is widely categorizable as “the Bible as literature,” and I won’t be overly concerned with theological or doctrinal questions. I rather approach the texts in the same way one would approach a poem or a novel, paying particular attention to key words, images, formal structure, and so on. I’ve taken Robert Alter as a guide in this regard, and most of the readings given in what follows use The Literary Guide to the Bible, edited by Alter and Frank Kermode, as a jumping off point. Because I’ll be using a literary approach, moreover, I’ll be reading the King James Version of the texts, as it is the translation with the highest literary merit.

Several assumptions accompany this way of reading, not the least of which is that the Bible is a unified whole. While this is how the Bible has generally been read since the formation of the canon, much scholarship of recent centuries has devoted itself to finding the “seams” between and within the various texts, and it is certainly true that a great variety of material has been woven together in each biblical book and in the construction of the Bible as a whole. The tools of criticism can be used to uncover the “archaeology” within a text, and if taken far enough eventually call into question the unity of the whole, which looks more and more like a conglomeration of disparate parts. While I don’t wish to discount the usefulness of much of this scholarship, the tendency to reduce the Bible to a mass of incongruous elements strikes me as, at best, one sided. As Alter argues in his introductory essay to The Literary Guide to the Bible, “scholarship, from so much overfocused concentration on the seams, has drawn attention away from the design of the whole.”

And there are good reasons to view the Bible as a coherent whole. For one thing, the very act of canonization unifies the texts, which are bound together because they were understood to be congruent. Moreover, the highly allusive nature of the texts tends toward integration. As Alter puts it, the Bible, “because it so frequently articulates its meaning by recasting texts within its own corpus, is already moving toward being an integrated work, for all its anthological diversity.” This unity has been the work of writers, redactors, and readers throughout history, and it is no violation of the texts as they come down to us to read them in this way, and it is, to my mind, vastly more interesting and imaginatively fulfilling to do so.

I should also be clear that I don’t approach the Bible in this way because I consider theological, legal, historical, or other readings invalid, though I am averse to all forms of fundamentalism. I am simply inclined to find literary reading imaginatively, and indeed spiritually, more fulfilling than most other approaches. I don’t consider other ways of reading as mutually exclusive with the literary approach, moreover, and I agree with Alter that other methods benefit immensely from attending to the literary features of a text. In the end, my goal is to deepen my relationship with the Bible by approaching it as a work of and for the imagination, and if doing so can be of interest to others, all the better. As I’ve said, I’m using the Alter and Kermode volume as a jumping off point, but the readings given here follow my own instincts, which are undoubtedly flawed in many respects.

That said, we’ll start, naturally enough, with Genesis, which I’ve broken up into several parts given the length of the book and especially the imaginative density of its first sections.

Genesis 1-11

The central theme of Genesis is fertility. As J. P. Fokkelman explains, the keyword of the book is toledot, meaning “begettings,” from the root yld, used for mothers (yaldah, “she gave birth”), fathers (holid, “he begot”), and children (nolad, “he was born”).1 The book opens with an initial explosion of generation with the two creation accounts, in which forms proliferate in ever greater fecundity. Creation is itself a kind of fertility, or perhaps we had better say that fertility is a form of creation and that every subsequent act of generation is itself a reflection of the primordial creative act of God—the fertility of humanity and of nature is an extension of God’s creative fertility.2 Indeed, as Fokkelman points out, the phrase “these are the generations of the heaven and the earth,” appearing in Gen 2:4, refers to the first creation and suggests boldly, though obliquely, that creation emerges from a kind of divine sexual act.

There are important differences between the two creation stories, however. Perhaps most striking in the first account is its orderliness. The spheres of being are increasingly articulated, with humanity coming at the end, as a pinnacle, in male and female, a suggestion of their fruitfulness as a reflection of God’s own fertility. Humanity’s vocation is laid out immediately: “And God blessed them, and God said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth” (1:28). Given the concern with harmony and fertility of the text as a whole and the first creation narrative in particular, the command to “have dominion” over the creatures would seem to indicate that humanity is supposed to continue God’s creative work of harmonious multiplication. Each creature has its own appropriate sphere and is to be fruitful within in, and humanity has the opportunity to facilitate that process.

The second creation account is messier, more ambiguous. Humanity is not depicted as obviously the pinnacle of the creative process. Still, Adam is in many respect central. We find him dwelling in a land of abundance, by rivers where flower trees of supernatural aspect, and he is placed there to tend the garden, further reinforcing humanity’s role as stewards of this creative fertility. God forms the animals for Adam and brings them to him so that he might name them, allowing him to further participate in creation.

Then, of course, comes the rupture, when the serpent convinces Eve to eat of the apple; she convinces Adam to follow suit, and the results are disastrous. The first thing Adam and Eve do is sow fig leaves together to make clothes, and they hide from God in their shame and fear. On discovering them, God bestows curses directly related to fertility: the earth is cursed, and through it Adam, so that the latter must work the land in pain just to survive, and Eve is cursed to bring forth children in sorrow and pain. The rupture with God is thus a rupture with fertility—both of land and sex—and death becomes a dominant theme, with famine and death in childbearing strongly suggested. It is also the first instance of enmity between humanity and other creatures, with the snake cursed to fight against Eve’s offspring.

Nevertheless, fertility is maintained. This point is made by Adam’s granting his partner the name of Eve, roughly translated as “life” or “the mother of all living,” directly after God pronounces the curses (prior, Eve was simply referred to as “woman”). God then makes them garments of skin and sends them out of paradise, setting a flaming sword to guard the entrance. The pair immediately begin to bear children, but the result is yet further rupture when Cain murders Abel, leading to another curse upon the earth: “When thou tillest the ground, it shall not henceforth yield unto her its strength” (Gen 4:12), though here the curse appears primarily to apply to Cain. Again, however, fertility is not diminished, and Cain becomes the father of a vast lineage. Here begins the long genealogical lists, which have baffled and annoyed many. Such lists are perfectly consonant with the concerns of Genesis, however, and Fokellman points out that they represent a flourishing of human fertility, the proliferation of names representing a success in the command to be fruitful and multiply. That they are long and repetitive only reinforces this point.

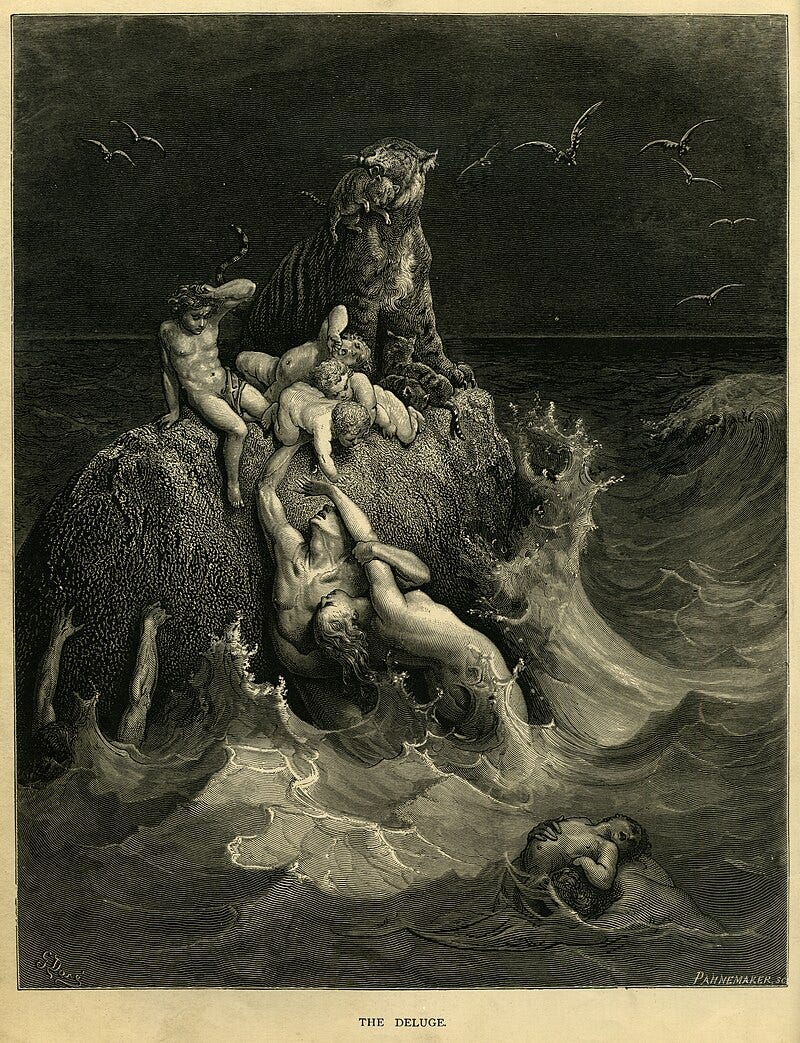

Nevertheless, we find wickedness once more interfering with human fertility, for the earth becomes so filled with violence that God repents of creation and resolves to destroy it with the flood. Only Noah finds favor with him, and he tells Noah to build the ark, which will serve as a microcosm for creation, a seed from which life on earth shall begin again. The imagery and language of the flood story is a recapitulation of Genesis 1, from the wind and the waters to the creatures “after their kind.” This is perhaps the most dramatic instance of destruction in the Hebrew Bible, and one that indicates with no uncertainty that fertility is conditional. Water is an important symbol in this regard, for it can be an image of either life or death. In Eden, as with the many “well-watered places” throughout the Bible, water brings fertility, growth, life, society. In the flood, however, it becomes a force of destruction, and this duality of the image is repeated throughout the Bible. This suggests the fertility God bestows upon creation is not inherent to any part of the natural order, for even the most fecund elements can wreak death as a result of evil.

When the flood finally recedes, the rainbow becomes the image of a new covenant. This is appropriate given the bow’s connection between heaven and earth and its tendency to appear after rain has subsided and the sun shines out. This covenant is made not only with humanity, moreover, but with all the creatures of the earth. And yet we are left in doubt regarding the purity of this new creation, and God seems to be making concessions when he allows humanity to begin eating the animals, saying that “every moving thing that liveth shall be meat for you” (9:3).

What follows is a strange story in which Noah, having made wine and become drunk on it, lays naked in his tent. Ham is cursed for witnessing and revealing his father’s nakedness, while the other brothers walk backwards to place a blanket over Noah without seeing his exposed body. It’s difficult to know what to make of this story. One could read it as another instance of humane care versus exploitation or violence, with Ham not only failing to protect his father in a vulnerable state but also revealing that vulnerability to others. Yet the tale also parallels certain aspects of the second creation story, namely, Adam and Eve coming to recognize their nakedness and covering themselves with clothing. Moreover, both events occur after ingesting fruit (apple or grape). Noah’s story is oddly inverse to Adam and Eve’s, for Noah drinks the wine and becomes naked, as if he were returning to a state of innocence. It is thus strange that God seems to express disapproval that Ham speaks of his father’s nakedness.

Perhaps the story suggests the necessity of shame once humanity has come to know good and evil. Shame is, after all, a primary means of maintaining any moral order. For a being capable of evil, shamelessness is almost synonymous with wickedness, as the negative implications of the word suggest. God himself appears to approve of clothing when he gives Adam and Eve the garments of skin, which not only cover their “shame” (a common biblical euphemism for genitals) but also protects their bodies in a hostile earth and a violent world. Shame and clothing can perhaps be seen as analogical, then, since shame as a moral influence protects human beings from the violence they might otherwise inflict upon each other.

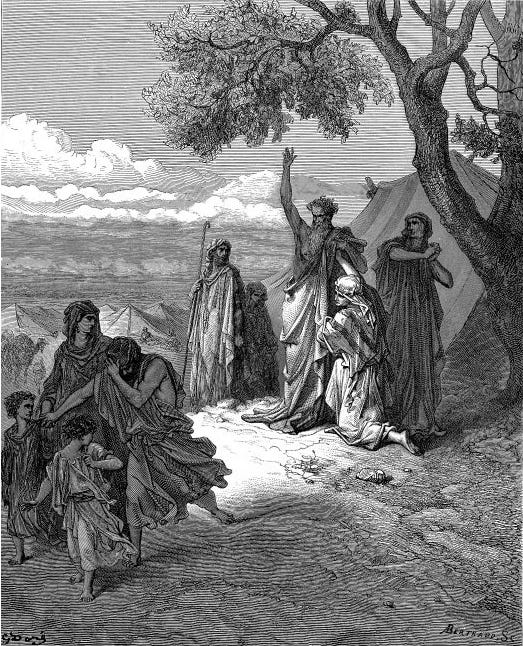

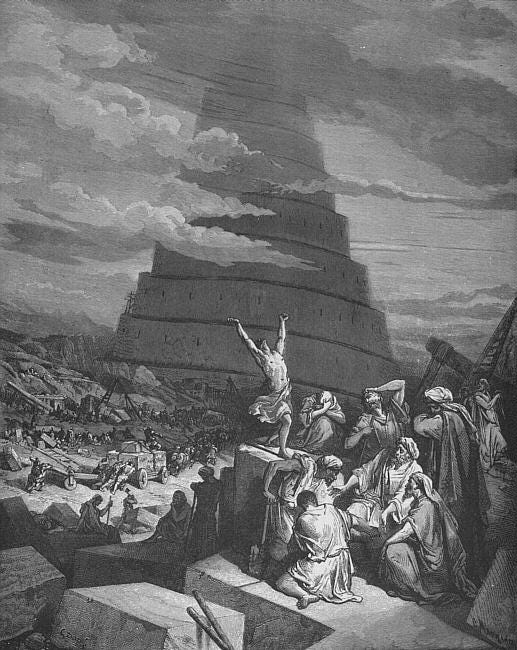

Despite the curse of Ham, Noah’s children proliferate, as seen in another long genealogical list, and the tower of Babel closes out the section before the introduction of the Abraham cycle. The story of Babel once more involves a rupture between God and society, this time with a technological angle. Humanity has become technologically adept enough that they believe they can rival God by building a tower to heaven. The brick has made them almost divine in their own estimation, so that God must scatter them and confuse their languages.

Technology is sub-theme of Genesis, and it frequently appears immediately after a rupture between humanity and God. Its first instance, the sown fig leaves, occurs after the eating of the apple. After God curses Adam and Eve, he gives them more practical clothing with the garments of skin. The first reference to tilling the earth occurs when God curses Cain, and then musical instruments and metallurgy are attributed to Cain’s descendants, with Jubal as “the father of all such as handle the harp and organ,” and Tubal-cain as “an instructor of every artificer in brass and iron.” Technology seems to largely occur, then, as a bulwark against death, as a kind of substitute for the intrinsic fertility of creation as God intended it. This is not to say that God appears against technology—he is quite happy to use it, after all—but that technology maintains a kind of ambiguity. It can be life-giving, as when the ark preserves Noah and the creatures of the earth, or it can be subversive to God’s will and lead to human hubris that must then be undone, as with the tower of Babel. The narrative seems to suggest, however, that technology arises to face problems of necessity that might have been otherwise avoided and that it is laden with intrinsic risks, primarily over-reliance upon it such that hubris results. As God forcefully reminds humanity over and over, he alone is the source of life, of fertility, and nothing can ultimately guarantee continuity save for reliance upon him.

J. P. Fokkelman, “Genesis,” in The Literary Guide to the Bible, ed. Robert Alter and Frank Kermode (Belknap, 1987), 41.

As an interesting aside, one finds similar themes of fertility as associated with the divine in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden, in which the protagonists become both healthy and good through gardening, where “the Magic” that makes the flowers grow invigorates them spiritually, physically, and morally. That “the Magic” is another way of saying God is rather obvious in the book, but it is God specifically as the life-giving origin of natural fertility.