Among the demons proliferating within the Jewish and Christian imagination, perhaps none—with the exception of Satan—has captured the modern imagination more than Lilith. Sometimes described as the first wife of Adam, Lilith is known a seductress leading men estray and for pursuing and killing children, particularly newborns, and amulets and charms meant to protect the young from her grasp are a common feature of Jewish history.

As Gerschom Scholem describes in Kabbalah, Lilith probably has her origins in Mesopotamian demonology, which describes male and female spirits of similar predilections, calling them “Lilu” and “Lilitu,” respectively. Some of these spirits attack men, while others seek to harm young children or women in childbirth. One demon of this kind is Lamashtu, the “bearer of seven names,” described as “seven witches,” who, among other destructive activities, seeks to kill children as a means of reducing the human population, the noise of which is so irksome to the gods.

Like Lilith, amulets meant to ward away Lamashtu were commonplace, and they have been found in Iraq, Iran, Syria, and beyond.1 These amulets usually depict Lamashtu in various forms, such as having a bird’s head and talons, though in later depictions she is consistently shown as a human, female figure with a lion’s head. Interestingly, she is sometimes depicted riding a donkey, which served a role similar to the Hebrew scapegoat in that, as John Wee puts it, the donkey “served as a decoy that dragged Lamashtu away by means of her own talons sunken deep into the equid’s back—thus turning the tables on her by taking advantage of her well-known modus operandi of ambushing and clutching onto her prey.”

One incantation describes Lamashtu thus:

She is fierce, fearsome, divine;

she is a leopard, the Daughter of Anu is a she-wolf.

Among the sassum-grass are her dwelling places,

among the alfalfa is her bedding.

She intercepts the running youth, she disposes of the hurrying son.

(As for the manner of) his capture,

she utterly smashes the tiny ones,

she makes the mature ones drink fetal water (i.e., amniotic fluid).– Old Assyrian (OA1) Lamashtu Incantation, lines 1–16 (translated by W. Farber)

As in this incantation, Lamashtu is frequently described as a kind of midwife or wetnurse, but one who causes stillbirths and whose milk is poisonous. In fact, a frequent characteristic of Lamashtu is that she does not conform to Mesopotamian notions of proper femininity, marked largely by maternal caregiving and affection. In his fascinating analysis, Wee suggests that Lamashtu may be an amalgamation drawn from caregiver malpractice or may represent retroactive resentment towards midwives and others charged with healing or caring for newborns who, by no fault of their own, were unable to protect or heal the children in their care. By this reading, the Lamashtu narrative represents a version of the witch story, in this case born from legitimate or illegitimate resentment towards caregivers who were blamed and demonized for the death of children, a common enough problem in a society experiencing high infant mortality.

Lamashtu’s characteristics bear a close resemblance to Lilith’s, the latter of whom may appear in inscriptions as early as the seventh or eight centuries BCE (though, Scholem notes, damage prevents an exact identification). Incantation bowls used to ward Lilith away appear in Ancient Babylon, frequently written in Aramaic and describing Lilith as a seductress and murderer of children. In the Hebrew Bible, however, she is mentioned only once, in Isaiah 34:14, which describes beasts and spirits that will destroy the land:

Wildcats shall meet with hyenas,

goat-demons shall call to each other;

there too Lilith shall repose,

and find a place to rest.

In the Talmud, however, Lilith appears with some regularity, though she is described more as a species of demon than as an individual. A demon having “the form of a lilith” is a female demon with a human face, long hair, and wings (Eruvin 100b; Niddah 24b). Shabbat 151b tells us that a certain rabbi prohibited sleeping alone in a house lest one be seized by Lilith (or a lilith).

A demon similar to Lilith is mentioned in the Testament of Solomon, which Scholem dates to around the third century (though other datings vary widely). The text is written from the perspective of King Solomon and describes the power of his magical ring, by which he gained dominance over the demons plaguing the building of the temple. The story is at once a kind of folktale and repository of demonology that may have been seriously used by those interested in exorcisms and magic. In the course of the narrative, Solomon captures a female demon who tells him that she is known by many names and makes her round throughout the earth by night, visiting women in childbirth and attempting to strangle or otherwise harm children. In this story, however, the demon is named Obizoth.

In the midrash, we again have Lilith appearing as a classification, with a “Lilith named Piznai” lying with Adam after he and Eve are condemned to death, and the pair beget male and female demons.

We find the most complete account of Lilith, and the one likely most recognizable to those familiar with the demoness, in the Alphabet of Ben Sira, which was probably written in the geonic period (sixth to eleventh century CE). It is in this work that Lilith is described as the first wife of Adam, created at the same time as him from dust. They have a dispute, however, over how they should lie together:

They [Adam and Lilith] promptly began to argue with each other: She said, “I will not lie below,” and he said, “I will not lie below, but above, since you are fit for being below and I for being above.” She said to him, “The two of us are equal, since we are both from the earth.” And they would not listen to each other. Since Lilith saw [how it was], she uttered God's ineffable name and flew away into the air.2

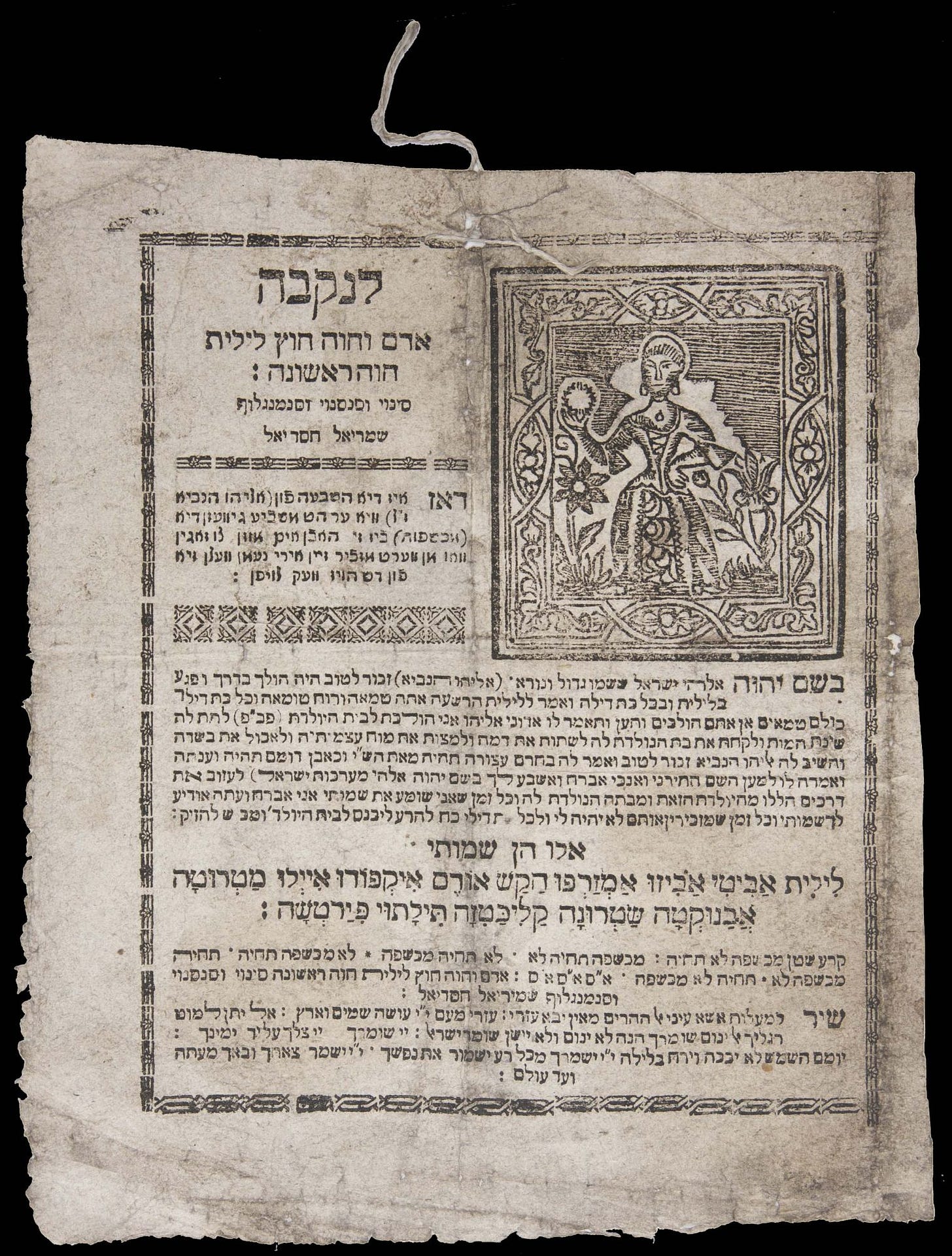

God then dispatches three angels, named Sanoy, Sansenoy, and Samangelof, who follow Lilith and threaten her with the death of her children, and then with drowning, if she does not return to Adam. She replies that she will not return, declaring that she was “only made to sicken babies,” and that she will have power over them for eight or twenty days, depending on whether they are male or female. She agrees, however, that where she sees the names or images of these angels written on an amulet, she will not there overpower the child.

This story draws on the earlier idea that the two creation accounts in Genesis involve two different women, the second of which is Eve. Ben Sira expands on this idea in his account of Lilith, and Scholem holds that this story is meant to retroactively explain already-existing practices in which amulets were made to keep Lilith at bay.3 Similar stories exist in Christian literature, in which the angels are replaced by three saints with similar names: Sines, Sisinnios, and Synodoros.

In Kabbalah, Lilith’s role as infanticide and seductress are fused. She is said to visit men in their sleep, causing nocturnal emissions, which she uses to beget hoards of demons. The demon sons of such unfortunates may even appear at their father’s funeral to claim their rights of inheritance and harm competing heirs, a belief that led to the odd taboo by which eldest sons were prohibited from attending their fathers’ funerals lest they be harmed by their demon siblings. In this role as the queen or mother of demons, Lilith is also considered the wife of Samael, the Kabbalistic name for Satan.

In the sixteenth century, superstitions regarding Lilith included the belief that an infant laughing in its sleep was being entertained by the demoness, protection from whom was effected by poking the child on the nose. Children and women in childbirth were further protected by amulets containing the names or images of the angels ruling Lilith, or of Lilith herself bound in chains.

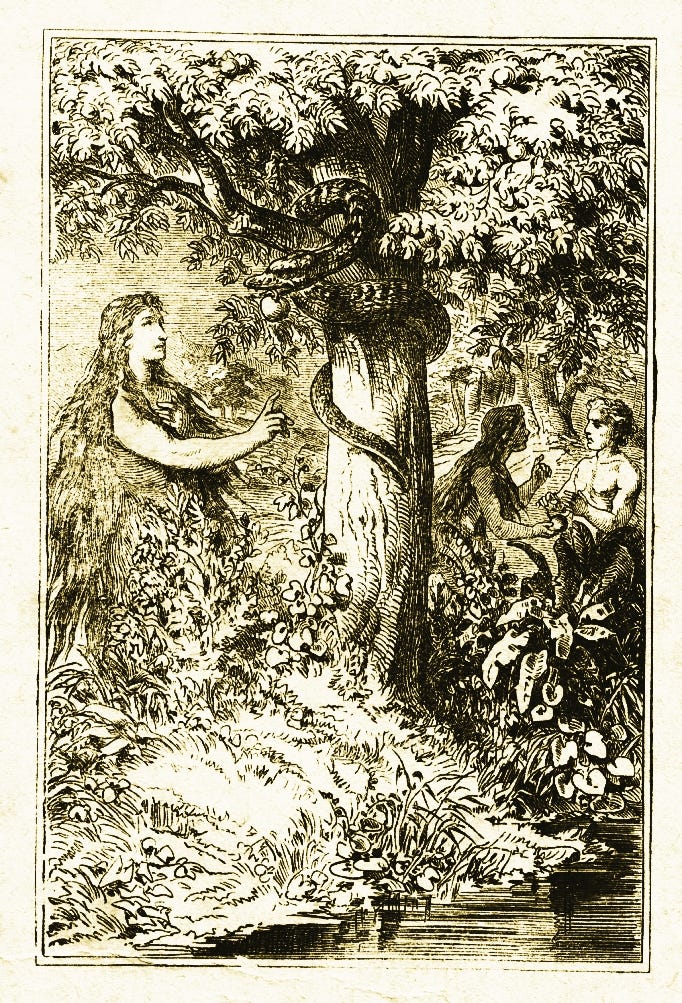

In the Christian world, too, Lilith makes numerous appearances, most famously as a half-woman, half-serpent figure in Michelangelo’s fresco The Fall of Man, in the Sistine Chapel. Here we see Adam and Eve being tempted by a woman whose legs morph into serpentine tails wrapping around the Tree of Knowledge; commentators have largely identified the figure as Lilith.

In more recent centuries, Lilith has been the inspiration for any number of paintings and works of literature. In the later nineteenth century, Dante Gabriel Rossetti dedicated to her both a poem and a painting. The latter imagines the eroticism of the figure in contemporary terms and is accompanied by a poem, which was first titled “Lilith” but was later changed to “Soul’s Beauty”:

Of Adam’s first wife, Lilith, it is told

(The witch he loved before the gift of Eve,)

That, ere the snake’s, her sweet tongue could deceive,

And her enchanted hair was the first gold.

And still she sits, young while the earth is old,

And, subtly of herself contemplative

Draws men to watch the bright net she can weave,

Till heart and body and life are in its hold.The rose and poppy are her flowers, for where

Is he not found, O Lilith, whom shed scent

And soft-shed kisses and soft sleep shall snare ?

Lo! as that youth’s eyes burned at thine, so went

Thy spell through him, and left his straight neck bent,

And round his heart one strangling golden hair.

In contrast to the deceptive beauty of Lilith, Rossetti images another female figure, painted in Sibylla Palmifera and again accompanied by a poem, entitled “Soul’s Beauty”:

Under the arch of Life, where love and death,

Terror and mystery, guard her shrine, I saw

Beauty enthroned; and though her gaze struck awe,

I drew it in as simply as my breath.

Hers are the eyes which, over and beneath,

The sky and sea bend on thee,—which can draw,

By sea or sky or woman, to one law,

The allotted bondman of her palm and wreath.

This is that Lady Beauty, in whose praise

Thy voice and hand shake still,—long known to thee

By flying hair and fluttering hem,—the beat

Following her daily of thy heart and feet,

How passionately and irretrievably,

In what fond flight, how many ways and days!

For Rossetti, then, Lilith represents the dark side of beauty and eroticism, especially its deception and self-obsession, its tendency to lust and narcissism. He does not condemn beauty as such, however, for Sibylla Palmifera and “Soul’s Beauty” suggest a spiritual beauty, which may be incarnated in physical form but which always leads up to higher things, to “one law.” These two figures are two sides of beauty, the one demonic and the other divine.

Rossetti’s poem also inspired another Pre-Raphaelite, John Collier, who in 1887 painted his own version of the demoness, simply titled Lilith, a work arguably bolder in its presentation of Lilith’s dark eroticism.

Less than a decade later, George MacDonald would use the demoness as the eponymous villain of his fantasy novel Lilith, published in 1895, an imaginative tour de force in which one Mr. Vane leads an army of “Little Ones” (children who never age) against the malicious sorceries of the demonness, who is ultimately defeated and redeemed.

As should by now be obvious, Lilith, like Lamashtu, displays many complexities indicative of historic gender relations. Her conflict with Adam over the nature of their sexual union (and of the relative valuation of men and women) as given in The Alphabet of Ben Sira is the most explicit in this regard, implying with misogynistic aplomb that a woman who does not submit is a child-killing demon. With such a background, it is unsurprising that since the twentieth century, Lilith has taken on a new role as a feminist symbol. By this reading, Lilith represents the independent woman seeking equality, who will not be sexually or socially subservient. This led, in 1976, to the founding of a Jewish feminist magazine named after Lilith, an inaugural essay of which provides something of a manifesto for her role as feminist icon. Today, much popular discourse around Lilith retains the feminist perspective, as any internet search of the name shows.

Such creative reworkings of traditional narratives seem inevitable with a figure as multifaceted and with as much cultural resonance as Lilith, and it is no wonder that she has stuck so well as a feminist figure. Whatever permutations and significance she may take on next, it is likely that she will be with us for some time, reflecting our fears, desires, grievances, and prejudices.

As described by John Z. Wee: https://harvardlibrarybulletin.org/lamashtu-amulet-portrait-caregiver-demoness#_ftnref7.

https://jwa.org/node/23210

Gershom Scholem, Kabbalah (New York: Quadrangle), 357.