Cărtărescu's Dreams

Some thoughts on Solenoid

After many hours of reading, I have recently entered the final section of Mircea Cărtărescu’s mammoth, beautiful, disturbing novel Solenoid. The book has left a deep impression on me, both as a great work of art and as an inspiring call to a deeper exploration of the imagination through writing. While Solenoid’s narrator seeks freedom from the prison of his earthly existence, the book displays through its own processes how we might escape the prison of our own assumptions and narrow approaches to creativity and the imagination.

As with Cărtărescu’s other works, Solenoid, his latest novel to be translated into English,1 is deeply surreal, eschewing linear plots, traditional narrative forms, and solidified realities. Everything is in flux as the narrative proceeds in complete freedom through the landscapes of the imagination, from which nothing is excluding. Diary entries, dreams, memories, inventions, history, reading notes—everything blends into each other yet remains coherent, centered on the narrator and the obsessive recurrence of certain themes.

The novel follows the life a parallel version of Cărtărescu, one from an alternative timeline in which he was crushed by his first public literary reading and subsequently never became a published writer, instead remaining forever a teacher at a dysfunctional school in Communist Bucharest. He shuttles between work and a large, “boat-shaped” house, where he spends his free time writing his “anti-novel,” the text of Solenoid. In it he includes reflections on his childhood, his dreams, his relationships, his wild colleagues, and every facet imaginable of his interior life. Such are the elements of “normal,” day-to-day reality within the book. But nothing in Solenoid is predictable or as it seems. From the very first pages, when the narrator’s bellybutton begins to expel twine wrapped around his umbilical cord at birth, the book unfurls into ever more oneiric territory.

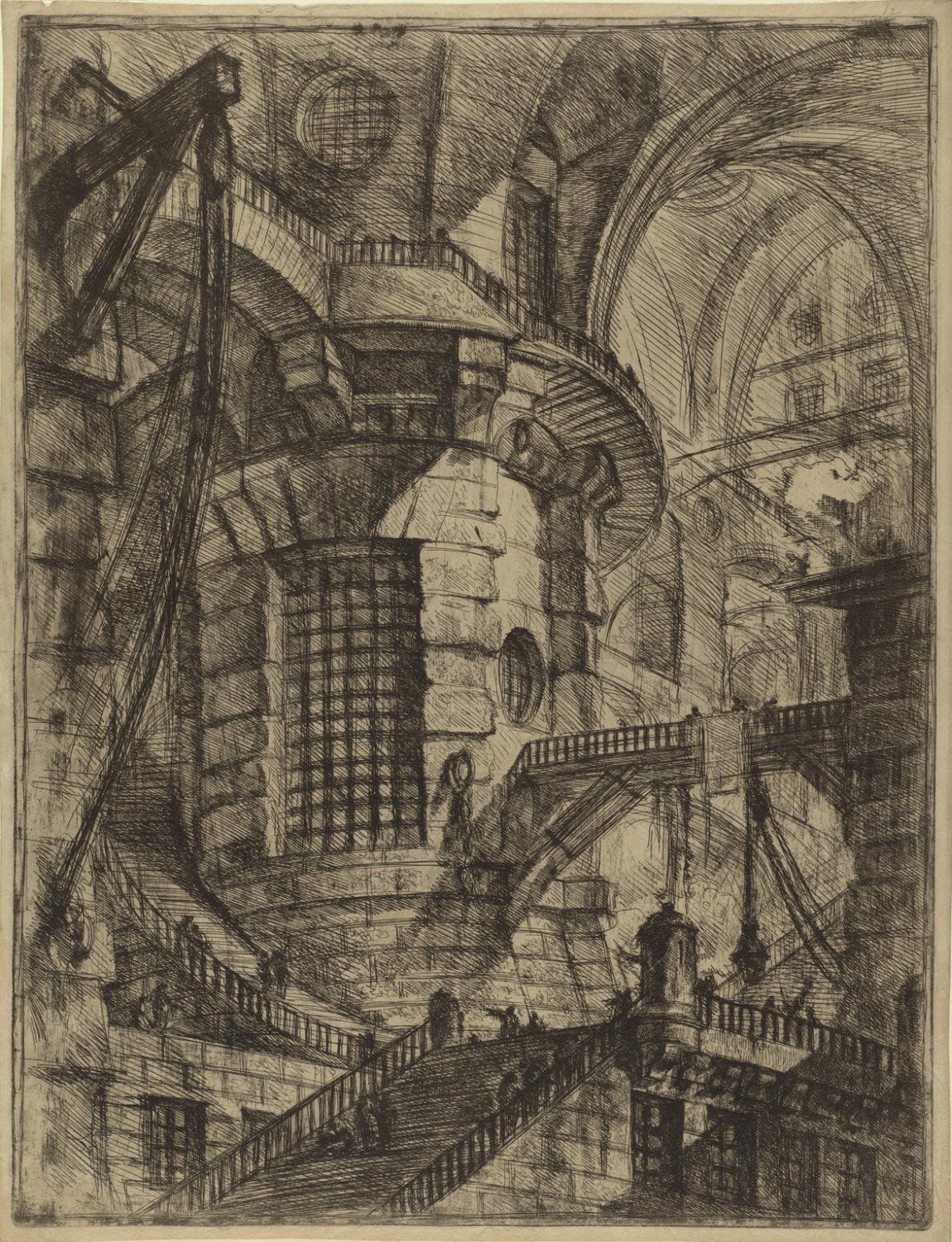

It is not worth attempting to summarize this territory; it is too vast. Moments of banality open into moments of dizzying horror or beauty: A door in an abandoned building opens to reveal a museum of giant parasites. A plant devours the face of a schoolgirl. A scientist asphyxiates himself to explore thanatoid realms. A couple embraces while levitating two feet above their bed. The book reads in certain respects as a long series of episodes, each connected thematically to the others and sometimes meeting up with them in time or space. Yet the themes of the book are consistent, and one is overwhelming: the gnostic longing to escape the imprisonment of a terrifying reality. It is a bleak theme, and one that Cărtărescu carries as far into the darkness as one might imagine. The whole world becomes a series of torture chambers in which humans are mites on the body of an angry or indifferent god. But there are chinks, clues, puzzle pieces scattered throughout one’s life and one’s consciousness that must be gathered up, pieced together through long anguish and confusion, until one finds the hidden code that might lead to liberation, to escape. This escape is not imagined as a passage from one cell of the world to another, but as flight from the third dimension itself, into the fourth, into the hyper-space of a higher world, free from the endless suffering of birth and death.

Gnostic sensibilities have a venerable literary (not to mention religious) history, and Cărtărescu’s version is wildly unique in many respects, and his forays into mathematics (Charles Hinton and the fourth dimension recur regularly) are particularly fascinating. The book’s bleakness is appropriate to such a sensibility, but it is at times also one of the work’s greater burdens. It is difficult to sustain, after all, such darkness without occasionally sounding like a petulant teenage edgelord. I found myself rolling my eyes at certain long passages about the torture chamber of reality or the mockery of dark, unimaginable gods. There are sentences that belong in the (for me) always cringe- or laugh-inducing excesses of Lovecraft.2 Luckily for us, such passages are a minority in the book, and they are overcome by the fascination, the beauty, and even the humor of the work as a whole.

But, as I’ve said, I haven’t quite finished the book, and I didn’t sit down to write a review, but rather to talk about why I consider it one of the most valuable books that I have read, if only for myself and my own creative process. For whatever one thinks of Solenoid or Cărtărescu’s other books, he is undoubtedly one of the great explorers of the imagination freed from constrains of genre or premeditation. As he has said in multiple interviews, he writes his books completely impromptu, with no prior planning whatever (and frequently, if you can believe it, without revisions).3 As much as I have loved Solenoid, I have an even higher regard for the freedom it has inspired in me as a writer, for it shatters boundaries regarding what is possible and what is permissible. There is no reason, after all, that we ought to keep writing within strict boundaries of novel, or essay, or review, or whatever. There is no reason to divide fiction from nonfiction (and such divisions are always porous anyway), to exclude dreams, hallucinations, notes, history, philosophy, revelations, or dairies from storytelling. The imagination is boundless, unfenced, infinitely fecund, and writing can be a vehicle for its free exploration, for discovering that space where all things, fact or fiction, mingle.

What is most astonishing, I think, when one engages in this kind of practice, is that coherence begins to emerge as one writes, but organically, as if the imagination responds to one’s presence and offers itself in the form of correspondences, in themes, in messages. These are not unlike the clues Solenoid’s narrator seeks scattered throughout his life: They are messages of a higher order, a wider dimension. This is writing not just as craft (though it can of course include it) and certainly not as communication of prior organized points, but writing as a spiritual practice, as a process of discovery, of dreaming. As Julian Semilien has said, Cărtărescu is “eminently writable”—he frees us to become explorers ourselves, untrammeled by the fear of transgressing boundaries of taste or convention. Writing leads one to a higher perspective, in which memory and dream begin to fuse, where the banal facts of sensuous, physical existence are fused with higher meaning. As the narrator of Solenoid puts it (though with greater pessimism):

I looked more closely at the gift: it shone brightly in the summer sun. It was a round, gilded coin set in a metal frame. There were letters on both sides of the coin: A, O, R on one side, M and U on the other. Several days passed before I solved the mystery when on a whim I flicked the coin and it spun so quickly in its metal frame that it became a gold sphere, as free and transparent as a dandelion, with the ghostly word AMOUR in the middle. This is what my life is like, how it has always seemed: the singular, uniform, and tangible world on one side of the coin, and the secret, private, phantasmagoric world of my mind’s dreams on the other side. Neither is complete and true without the other. Only the rotation, only the whirling, only vestibular syndromes, only a god’s careless fingers spin the coin, adds a dimensions, and makes visible (but for whose eyes?) the inscription engraved in our minds—on one side and the other, on day and night, lucidity and dream, woman and man, animal and god, while we remain eternally ignorance because we cannot see both sides at the same time.

Art at its best offers us a means of coming closer to this integration, to this wider synthesis of vision, even if it is only one means of approach, and even if the final unity is not given to us to achieve in this life (if ever). For myself, following Cărtărescu’s method of allowing the imagination to proceed completely free has deeply transformed my own writing practice, of which this Substack is but one of the furthest and least fertile outliers. I have even found it difficult to sit down and write for this outlet lately (or for any more traditional space), as writing in such a linear mode feels almost a betrayal of that deeper practice, of that exploration which lately occupies so much of my free time. If I can make one recommendation, then, it is to read Solenoid, but even more to allow its way of engaging with the imagination to affect you, and to try to open the door of dreams, of free association, of wandering through the land of the imagination. It is a real, living place, after all, where everything speaks and responds to your presence and will in all likelihood speak not in generalities, but to you, yourself, both visitor and inhabitant of that wider, higher world.

At least until Theodoros makes its appearance next year.

What horrible geometries emerged from the slime-flooded sea, that human mind could neither describe nor comprehend! What twisted intelligence could make the glyphs of that monstrosity, of that squelching, horrid nightmare! (I honestly consider Lovecraft one of the most unintentionally hilarious writers of all time, especially when read out loud with some excessively dramatic panache).