It is a common feature of much Christian ascetic literature, particularly of the east, that the imagination is held in suspicion. On the one hand, this is entirely understandable, as a great deal of vice begins in the imagination, in the suggestion of images that stir up the passions, which if indulged become fantasies that finally manifest in action. A scrupulous ascetic might be better off shunning this interior world in order to avoid such temptations altogether. The deeper layers of mysticism, after all, go beyond the imagination, beyond all representation as such, and so there is no necessity that one engage with it in the pursuit of inner prayer.

And yet this suspicion of the imagination is one that risks being one-sided and marginalizing legitimate forms of contemplation. Luckily, this hostility is one that has been balanced in various ways within the Christian tradition. Ignatius of Loyola’s spiritual exercises, for instance, seek to deepen one’s faith and commitment to Christ by entering into episodes from Jesus’s life in an engagement with all the senses of the imagination. Even in strict ascetic circles, as in the monasteries of the Egyptian dessert where dwelt the likes of Evagrius Ponticus, material evidence suggests that the imagination and its artistic uses were not wholly rejected. For more recent works, one only need consider George McDonald or C. S. Lewis to see the potential for the imagination to serve—rather than distract from—religious and spiritual direction.

This complexity of attitudes reflects the complexity of the imagination itself, which represent a sphere of human life so unbounded, so vast and strange to those who begin to seriously engage with it, that it can strengthen any tendencies, good or bad, to which it is made to serve. For the undisciplined, it is frequently the locus of distraction and sin. And yet the disciplined use of the imagination has the potential to open up vast corridors of spiritual experience and creative life, and this life is one that belongs to all human beings, all of whom share in it to some extent, even if a materialistic culture and the disillusionments of adulthood have dulled them to it.

Following Ignatius of Loyola, I think there are few better avenues for imaginative contemplation than scripture. Entering the world of the Bible by placing oneself in it is already to some extent what reading scripture is, and to spend time exploring these scenes in the full extent of one’s interior senses is simply an intensification of this kind of reading, a form of lectio divina, in fact, by which we may enter more fully into the text, and the text may enter more fully into us.

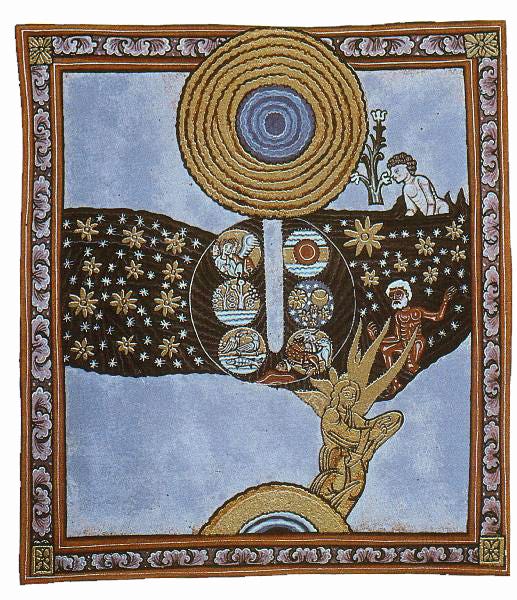

For myself, the creation stories of Genesis are particularly fertile ground for such exercises, and I have spent a considerable amount of time in my imagination with the seven days of creation and the lilting boughs of Eden. In contemplating Genesis 1, I’ve found that the images evoked begin to form themselves into patterns, intertwinings of above and below, land and sea, light and darkness. Fish swarm, flying through the waters in parallel to their avian counterparts, and on the newborn earth grows forth a tree. Into this mandala is born the figure of a human being, a capstone of sorts, and to my surprise he is born not merely among the lopping, crawling beasts, but is placed stretched out upon the tree as Christ is laid upon the cross, tying together much of the Christian story and suggesting cosmic resonances in the New Testament narratives. This human being, this lynchpin, pulls together all the colored strata of the world, becomes the world in miniature and joins it to himself.

At least, that is the avenue that my particular imagination takes, and it is no surprise that it reflects my own theological predilections and education, mirroring in certain respects the thinking of church fathers like Origen and Maximus the Confessor. And yet it deepens my understanding and nurtures not merely an abstract, philosophical engagement with such ideas, but an intuitive, creative one. This is of immense benefit, and it is, I believe, closer to the realm of genuine spiritual experience than can be arrived at by simply mulling over ideas that one has read.

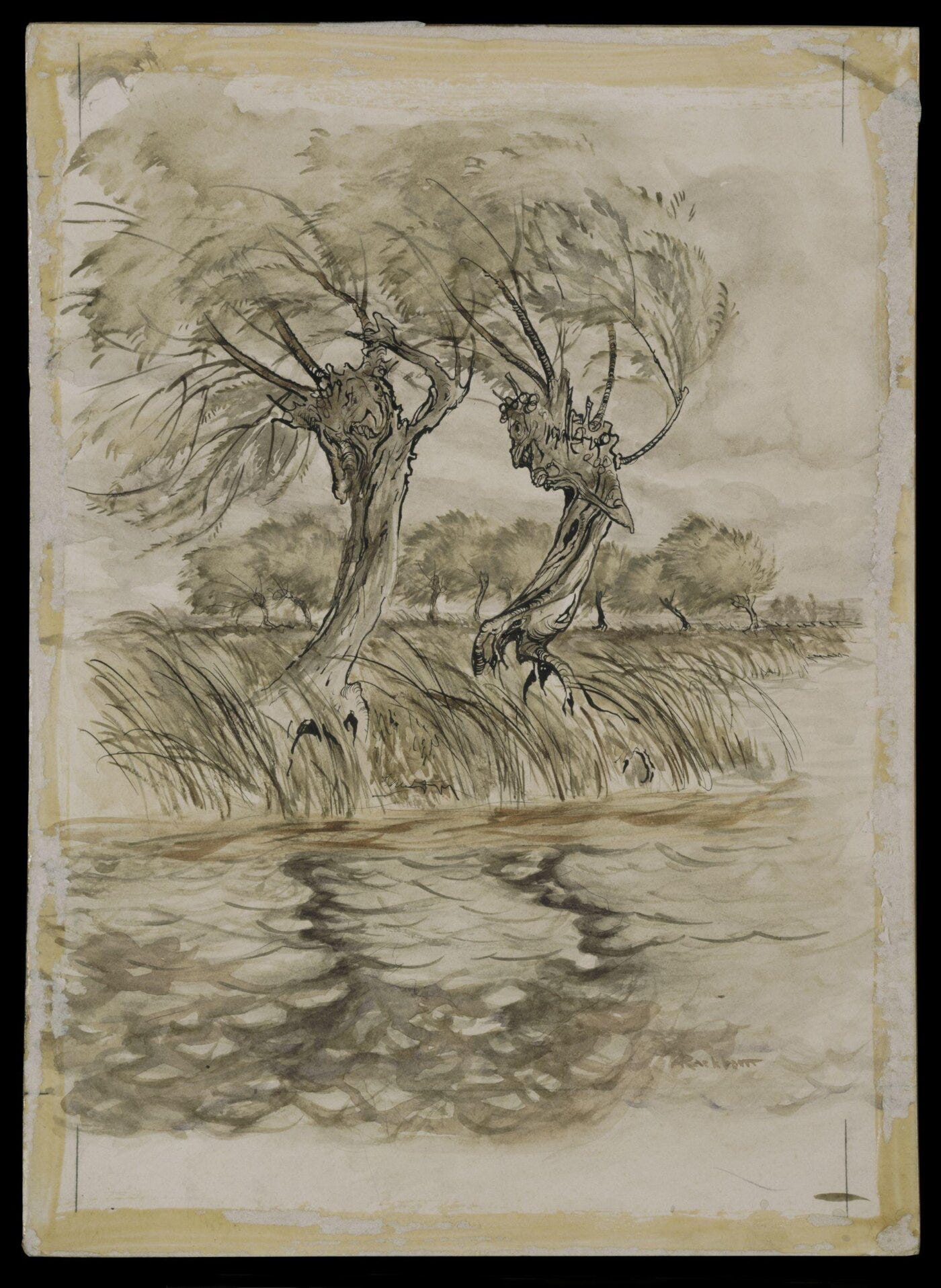

Such imaginative outings have also born unexpected fruit not merely in my reading scripture, but in reading all sorts of literature, which I find merges into the landscape of the biblical world. In a recent rereading of The Wind in the Willows, for instance, I recognized the river—that “sleek, sinuous, full-bodied animal”—not as some mere representation of an English stream or the idiosyncratic invention of a banker, but as born of the very waters which made lush the banks of Eden, the waters of life, by which the righteous tree is planted, where its leaf shall not wither. This river runs, I find, in various forms throughout the Bible, but I did not expect to find it here, whispering its stories to the likes of Rat and Mole until it reached at last the “insatiable sea.” And yet, on considering, I find it no surprise at all, for those rivers of our innocence are a spiritual place, a place of the imagination and yet higher, by which one may walk wherever there is life and beauty, truth and peace. Even the creeks that run nearby my own abode in the sensory world partake to some extent of those mountainous waters, and also of Grahame’s loveliest of waterways.

I can only conclude from such reflections—to the extent that I think I can make any conclusions from such a nonlinear practice—that the imagination does not consist of discrete locations, but is one vast country, a country wherein lives all tales and horrors, literature and art, and which, in its peaks, touches deep spiritual spiritual veins of human life, and of the wider life that is in all things. Nor must the imaginative works and vistas produced in the imaginations of other religious traditions—or by those espousing no spiritual life at all—be sequestered from each other, even if the extent to which any individual may enter them be limited by difference or prejudice. For all speak of a common life and share to some extent in common sources. They are all ultimately compatible with the human. These landscapes have their light places and their pits, their heroes and their villains, and it is up to us to discern what fosters the good and what ought better to be avoided.

Of course, to what extent my own imaginative world coincides with others is a question I cannot answer, but I have to believe there is some overlap, or else communication between two minds could hardly be achieved. And whether the whole imaginative realm consists of a unity in itself, a real, independent world that we all partake of in our own ways I leave to the metaphysicians, though I have my own suspicions. Yet it is a life and world we can and I think ought to enter—in a disciplined, careful manner—so as to drink from those great waters and learn in a deeper way from those works of imagination that have long guided our species towards the truth.

I'm partway through writing a lengthy Substack series that attempts to trace the relationship between imagination and spirituality. Honestly, my impression at this point is that there is more consensus between Christians east and west than would first appear, at least in the Patristic era.